I recently received a phone call from the wife of the late Janusz ‚Baluza’ Kozłowski, to ask me if I could come and pick up the bass guitar which I had bought from him (at a party) a year or so before the stroke which effectively ended his performance career. It’s a lovely instrument – an Ibanez Roadstar II – perfectly playable but with a few signs of age and of course, having belonged to a legend of Polish jazz, with a history!

Janusz was a wonderful man, a truly great musician and a close friend, but even before we became friends we played together on several occasions – sometimes officially, sometimes at parties or jam sessions. I had been in Poland for three years, and was invited to a meeting. It was something to do with jazz, it was at the National Library and there were a hundred or so people there but to be honest, I had no idea what was going on. Since Janusz was also there, we chatted while he was outside for a smoke. I told him I felt completely out of place and didn’t know why I was there. He very kindly said “It’s very good that you are here – you’re part of the Polish jazz scene.”

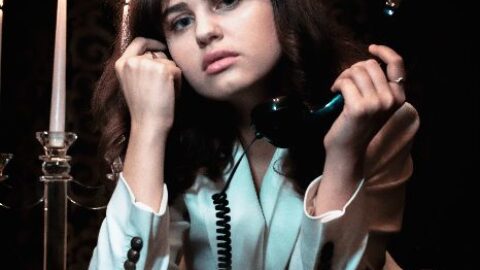

Janusz Kozłowski, celebrating 55 years on stage, April 2013

Don’t misunderstand me, from the very beginning the Polish jazz community has been very good to me and I have never felt pushed aside or excluded. However, that kind comment from Janusz marked a significant moment. I stopped feeling like an expat Brit, slightly out of place, and slightly displaced, both from my homeland and the country I was living in. Internally, it was the point at which I redefined Poland as ‚home’, and redefined ‚home’ as Warsaw.

Over the years Janusz and I played (and partied and drank) together on innumerable occasions, until the news that he had suffered a stroke, would probably be unable to play again, and had lost his memory. It later turned out that the latter two of these statements were not quite as they first seemed. What he had actually lost most of was his ability to move things from long-term to short-term memory.

The structure and function of memory and its role within the mind is mostly (but not entirely) understood these days. It’s a very complex subject, and it’s a long time since the doors of medical school slammed shut behind me, but I’ll try to explain at least in terms of what happened to Janusz. Short–term memory is what we use to live in the present. It’s very much like the RAM in a computer. It’s where your thoughts are now as you read this, and it lets you keep track of thoughts as they are relevant to your current activity. The filtered experiences and the thoughts and perceptions which these engender can be passed into long-term memory, to be recalled at a later date, assuming that the recall app is working properly.

The film industry has played with ideas of what happens when this is not in full working order, both in fiction and in fictionalised versions of real-life occurrences, so this is already floating around in the public consciousness to a certain extent. For Janusz, and for his wife and family, the reality was that although he retained or regained the ability to access his long-term memory, his present reality was not being passed over into long-term storage. This meant that he was aware of most of his life before the stroke, but in terms of continuing to create his flow of memories (which is how we measure our lives) everything stopped. This – as I’m sure you can imagine – caused constant mental and emotional confusion.

As a musician, short-term memory allows you to keep track of what you are doing. It keeps you in the context of the present, and allows you to move from this ‚now’ to the next. When you’re playing, it keeps track of where you are in the piece, how many choruses you have played, and reminds you of the high note you so spectacularly split 10 bars ago. Long-term memory is what allows you to play the music you have learned before, and frees your creative mind from the mundane physics of production to allow expression and improvisation.

Some time after Janusz had his stroke, when most of us had sadly decided that we had effectively lost our friend and colleague, I received a call from his wife. Would it be possible to buy back the bass guitar? She explained that Janusz was suffering bouts of severe confusion, because he couldn’t find his bass guitar, and was convinced that his teenage son had taken the guitar to sell it. The ‚teenage’ son is in his 40s I believe, and hadn’t lived at home for decades. If I could bring back the guitar, so that it could sit in the hallway where it had always sat, perhaps its absence would no longer trigger the confusion that was causing Janusz and of course his wife and family so much distress.

I said I would bring it immediately, but there was no need to buy it back. If it would help, I was happy for it to stay with them for as long as necessary. After all, I’m a singing trumpeter, not a bassist. I hurried over with the bass and met Mrs K at the door, expecting to give her the instrument and leave unnoticed. To my surprise, she said “Come in! Janusz is in the living room, he’s very happy that you’re here!”

Try to imagine how you would feel. One moment you are simply trying to help the wife of a friend who had disappeared into the confused depths of his damaged mind, probably never to resurface. The next, you’re walking in to be greeted by that same friend with a hug and a huge smile! He recognized me, and started chatting with me. He looked in good health (if somewhat heavier than before) and in good spirits. We talked about jazz, our friends, and even about some of the things we had done together. We did not talk about his condition. He was aware that something was not the same, but talking about it (at least with me) was not on the menu.

It was only after a few minutes of conversation, when parts of it began again from the beginning, that I began my long, slow journey of understanding the situation, aspects of which I have explained above. I left after chat, tea and cake, feeling utterly different to how I had been just an hour before. Of course, a few minutes after I had gone, for Janusz the visit had effectively not happened, but at least everything was where it should be.

For a while after this visit, I tried to work out some way that Janusz could perhaps come and enjoy a little of his old social life, possible even play a little. Very wisely, on each occasion when I suggested anything at all to Mrs K, she gently told me it wouldn’t be possible. Thinking about it, it would have been almost impossible to keep him from confusion and distress. Long-term memory would probably have allowed him to play, but how would he have known where he was, or even where he was going on the way there, and why, and for how long?

When people talk to me about art, or being an artist, I often think of Janusz, and how the stroke took his life and turned it into a short loop from which he never really escaped.

The conscious mind could be thought of as a conversation between the different types of memories – those being recalled from the instant ago when they happened; those at the beginning of the week or the beginning of the sentence; those from another age.

Art, whatever else it may be, is a product of mind. So what happens when the conversation stops?

Tekst i zdjęcia: Mark Shepherd

Redakcja

Informacje z kraju i ze świata - Wywiady - Felietony - Zapowiedzi wydarzeń artystycznych - Relacje z wernisaży - Projekty artystyczne -Patronaty medialne - Reklama - Prezentacja i sprzedaż sztuki.

Latest posts by Redakcja (see all)

- „Jak sprzedać mieszkanie i nie zwariować?” My już to wiemy! - 18 października 2018

- „Jak sprzedać mieszkanie i nie zwariować?” – twoim przepisem na sukces! - 20 września 2018

- Sztuka jako podróż sentymentalna. - 27 lipca 2018